.

One of my very long-term amateur interests has been the development and spread of language families. Probably because of where I come from and where I am — along with reasonably easy access to the relevant academic literature — most of my knowledge is about the Indo-European language family, and I have spent the holidays re-reading (for the third time), David Anthony’s fascinating study called The Horse, the Wheel, and Language. I learn so much each time I read this work, but the particular point that intrigues me right now is the development of personal names.

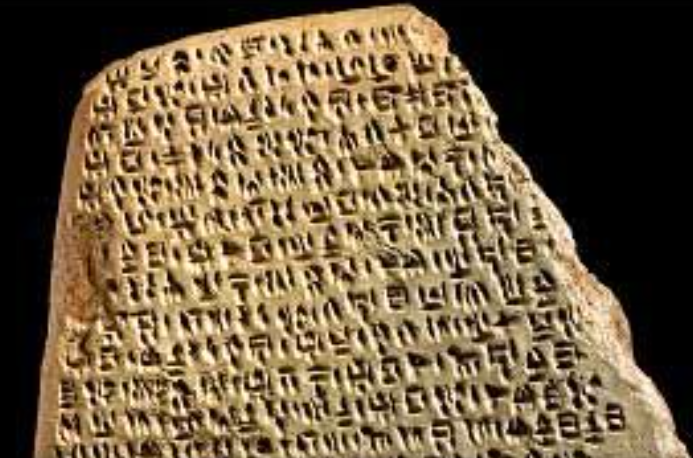

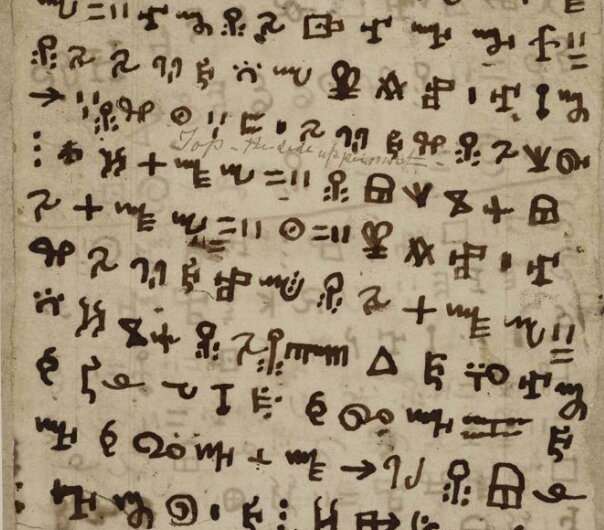

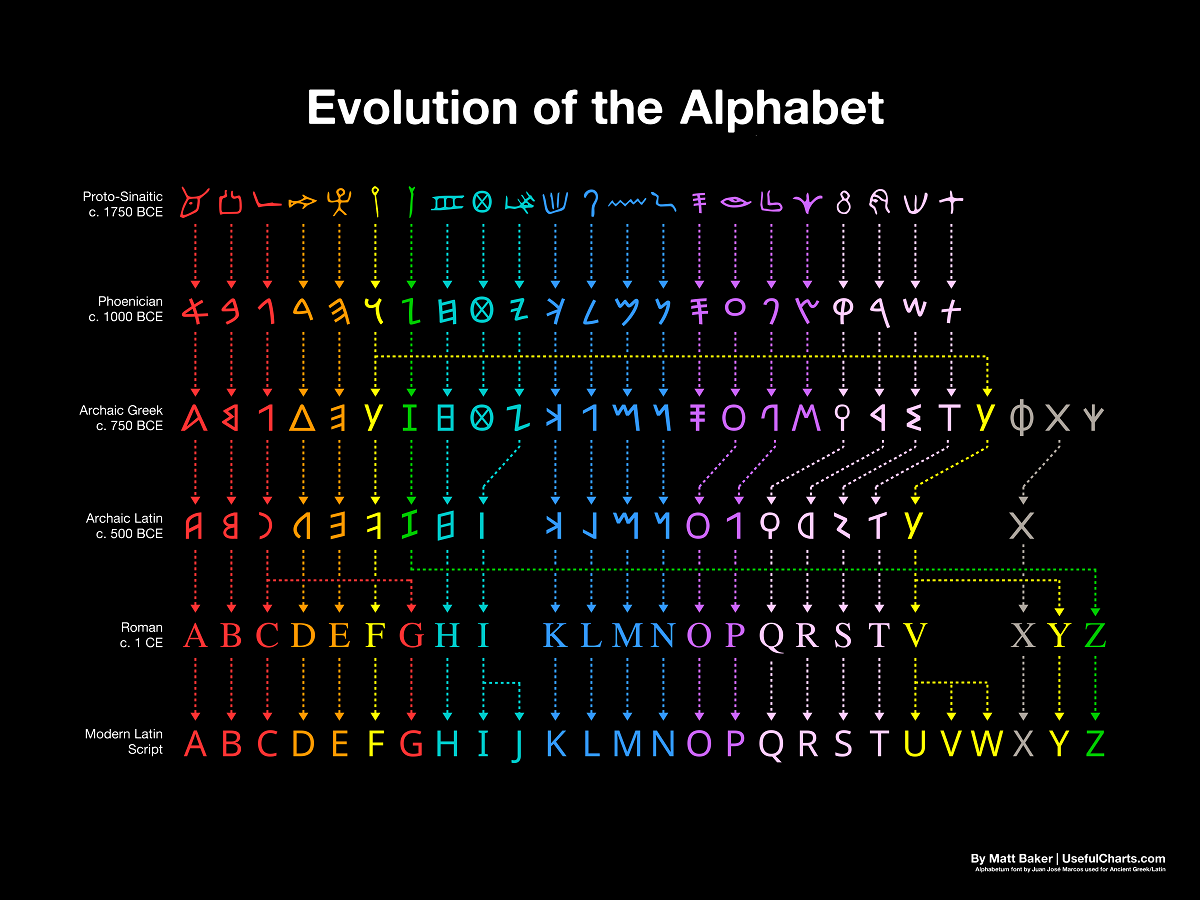

As I understand it, the first two names known in history are an Egyptian leader called Iry-Hor and a Sumerian called Kushim. Both of these lived a little before 3000BC, so about 5,000 years ago. However, these were clearly not the first names, just the earliest names that we can more or less accurately date from inscriptions and thus known to us. Obviously, we cannot ever find inscriptions from a period prior to the invention of writing (about 3500BC) but it seems equally obvious that people (some people?) had personal names well before that innovation.

I have read one theory that suggests personal names began to be used after the invention of agriculture when division of labour became more clearly defined. However, it is not difficult to imagine the value of personal names millennia earlier both in the hunter-gathering economy and as a part of everyday clan life. I doubt we can ever trace this without writing or inscriptions.

I also read that some scientists have determined that dolphins have personal names in the form of an individual “whistle” that they respond to. That led me to wonder whether any of our primate relatives call each other by individual names? Anybody know?

Posted by jakking

Posted by jakking